Window (SCL Group), 2018

UV degradation of archival board on aluminum composite

1900 x 2400mm

Bird feeder (Tortoise), 2018

Fiberglass, paint, window

860 x 1080 x 650mm

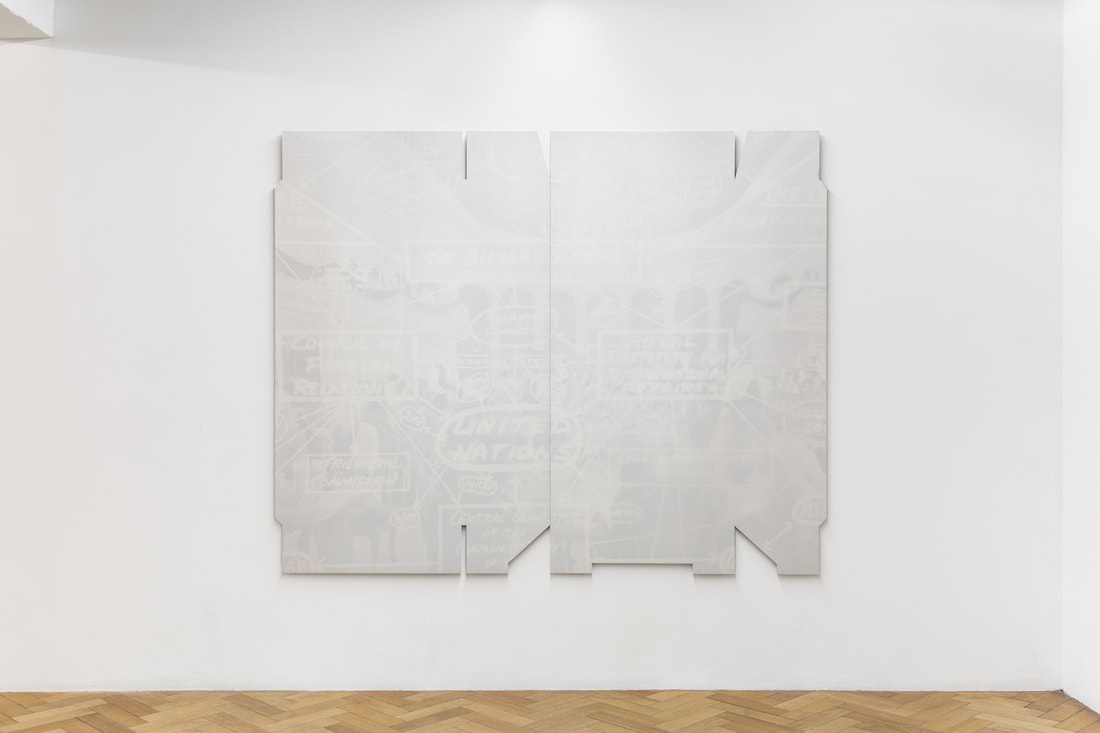

Window (Be our guest), 2018

UV degradation of archival board on aluminum composite

1900 x 2400mm

Bird feeder (Book depository), 2018

Poplar plywood, filler, paint, window

740 x 740 x 715mm

Window (Interface), 2018

UV degradation of archival board on aluminum composite

1900 x 2400mm

Bird feeder (Wolf), 2018

Foam, synthetic fur, fabric, resin, electric fan, paint, window

600 x 550 x 400mm

Bird feeder (Chest), 2018

Fiberglass, paint, salt, window

760 x 580 x 740mm

Bird feeder (Server cage), 2018

Steel, paint, bird whistles, window

600 x 585 x 1030mm

Bird feeder (Trough), 2018

Stainless steel, bronze, window

1200 x 300 x 300mm

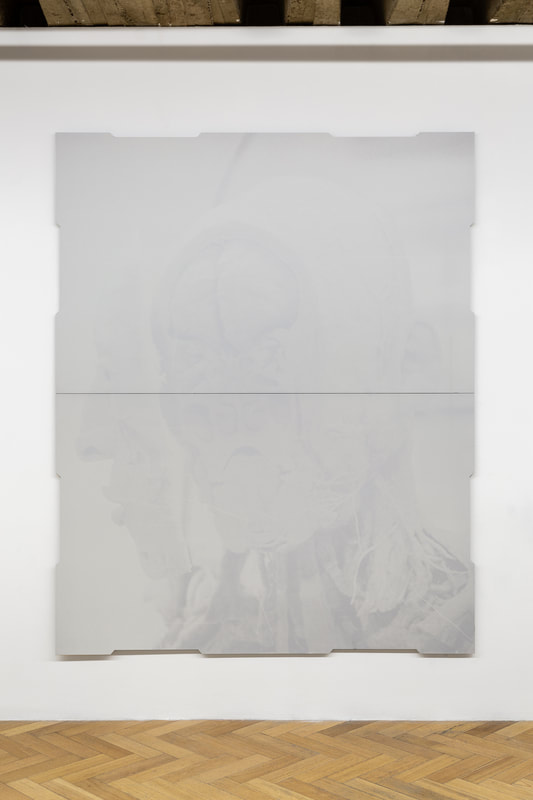

Window (The psychology of a half apple), 2018

UV degradation of archival board on aluminum composite

2400 x 1900mm

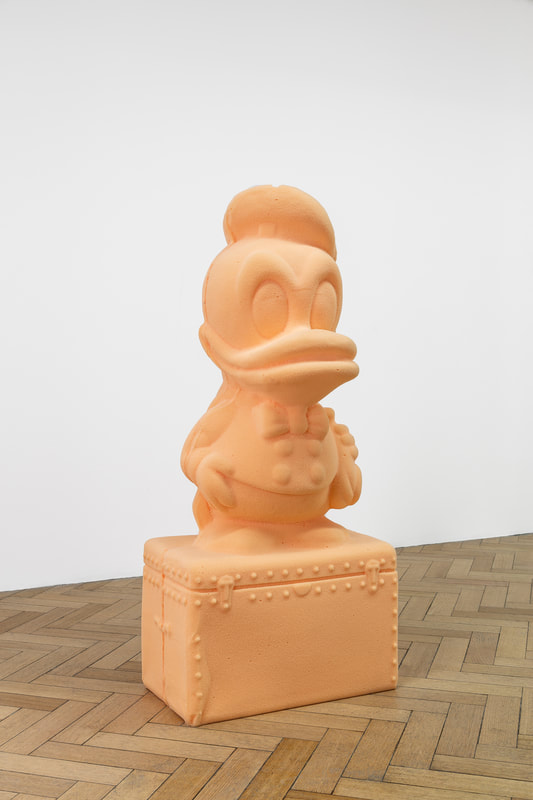

Bird feeder (Ritalin I), 2018

Polystyrene foam, filler, polyurethane coating, automotive paint, window

650 x 600 x 1200mm

Bird feeder (Casket), 2018

Wood, metal, fabric, window

1200 x 540 x 780mm

Window (Cambridge Analytica Office), 2018

UV degradation of archival board on aluminum composite

1900 x 2400mm

Bird feeder (Butter churner), 2018

Wood, steel, window

500 x 320 x 400mm

Window (Sun Microsystems), 2018

UV degradation of archival board on aluminum composite

1870 x 1450mm

Bird feeder (Money box), 2018

Foam, window

640 x 580 x 1400mm

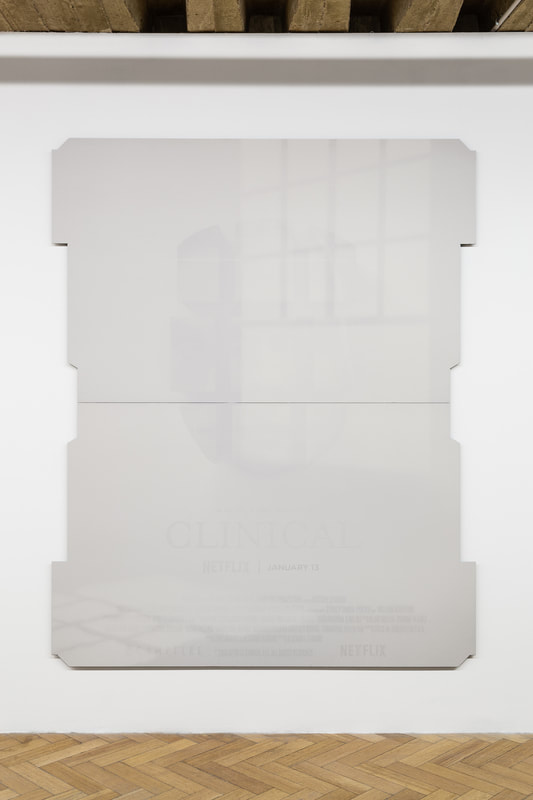

Window (Clinical), 2018

UV degradation of archival board on aluminum composite

2400 x 1900mm

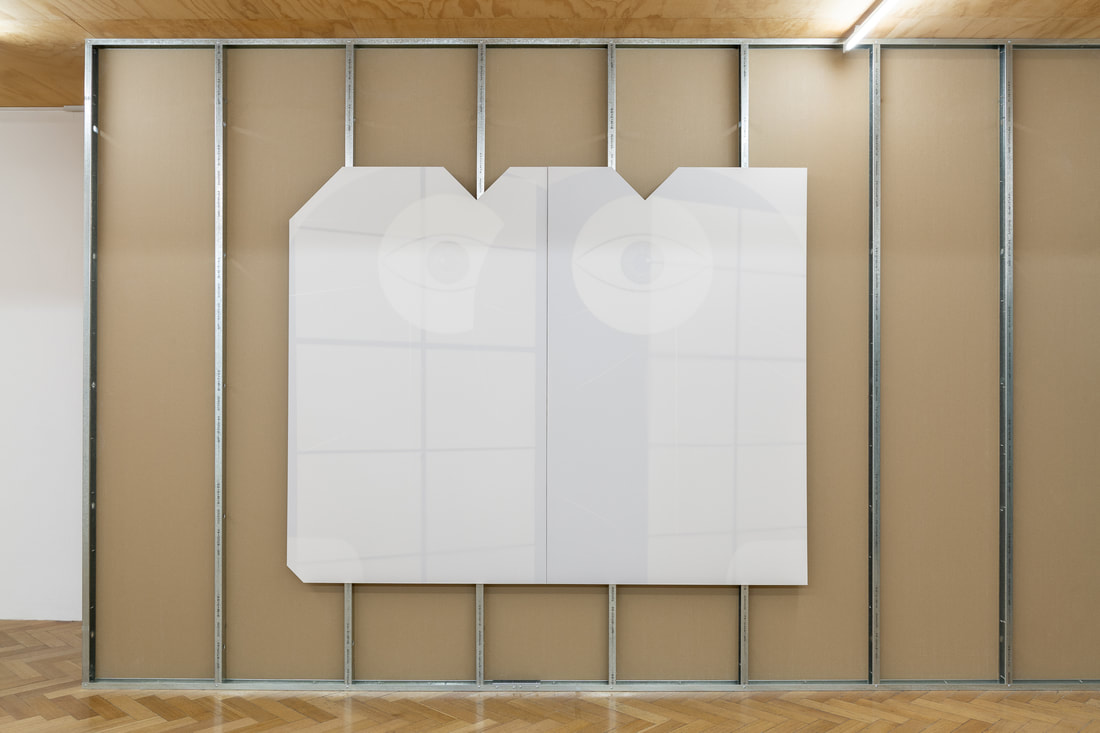

Window (Hydra), 2018

UV degradation of archival board on aluminum composite

1900 x 2400mm

Bird feeder (Safe), 2018

Safe, window

900 x 360 x 450mm

Bird feeder (Ritalin II), 2018

Polystyrene Foam, filler, acrylic paint, steel, window

680 x 800 x 400mm

Bird feeder (Chimney), 2018

Steel, wood, brick, cement, window

1075 x 710 x 2110mm

Window (Christopher Wylie T-Shirt), 2018

UV degradation of archival board on aluminum composite

1900 x 1190mm

Open Window Gavin Bell, Jarrah de Kuijer, & Simon McGlinn

Matterport 3D Showcase

Open Window

13 Sep – 3 Nov 2018

West Space

Close up any other rooms that you can, forcing the bird into one area of the home. Close off and cover any windows in the containment area except for one. is window should be opened as wide as possible. With some time, the bird will y toward the open window and back out into the wild. If significant cant time passes and the bird still hasn’t gone out the window, you can try to steer the bird using a large sheet. Hold the sheet in both hands with your arms raised like a ghost. Herd the bird toward the window without touching it, just as a cattle dog steers sheep through a pasture.

Inside opens to outside. Outside comes in through the window. Inside contains outside.

[INTERNAL WALLS]

In 9 of 12 societies where homes have separate bedrooms for parents, people prefer to have sex indoors. In cultures without homes with separate rooms, sex is more often preferred outdoors.

[SILENT READING]

They could exist in interior space, protected from outsiders by its covers, became the one’s own possession, one’s intimate knowledge, whether in the busy scriptorium, the market-place or the home. Eyes were drawn through the pages, while his heart searched for its meaning; however, his voice and tongue were quiet.

[SINGLE BEDS]

Among the modern North American Utku’s, a desire for solitude can seem profoundly rude.

American maximum security prison – highest form of punishment: solitary confinement. Prisoners commonly restricted to cells of 80 square feet, not much larger than a king-size bed.

[INFORMATION CONFIDENTIALITY]

Keep it secret, keep it safe.

The intensity and complexity of life, attendant upon advancing civilization, have rendered necessary some retreat from the world, and people, under the refining influence of culture, has become more sensitive to publicity, so that solitude and privacy have become more essential to the individual; but modern enterprise and invention have, through invasions upon one’s privacy, subjected people to mental pain and distress, far greater than could be inflicted by mere bodily injury.

Is it secret? Is it safe?

[VOLUNTARY TRACKING]

A pigeon came through my window. I knew it would, I opened it for them.

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. That’s how we think of it. If we can get out of the way, our guests can create more memories.

Science has demonstrated that free will is an illusion – people who are induced to believe this are more likely to behave immorally.

Interview between curator Patrice Sharkey and the artists.

Patrice Sharkey: Let’s begin with your starting point for Open Window. What are you currently thinking about and how have these ideas taken shape for this project?

Gavin Bell, Jarrah de Kuijer & Simon McGlinn: The title of the exhibition is Open Window. The window is a transparent boundary between the inside and the outside: a viewpoint from either out or in, an entry and exit for observation and light, but also a sort of vulnerability in terms of privacy and security.

This project feeds off our last solo at Gertrude Glasshouse titled, Entertainment is like friendship, that dealt with the growing tension of the public’s trust of personalising algorithms working on content platforms like Facebook, Google and Netflix, and a wider anxiety and acceptance of one’s digital footprint. The title, Entertainment is like friendship, is paraphrased from the Netflix culture text that the company has made available for potential employees. The text alludes to the concept of the content provider becoming so intimate with its consumers through big data that they are like a friend to their consumers.

Your work regularly weaves together a wide range of referents (virtual, visual, material and theoretical etc). Can you describe some of the key symbols, stories and objects featured at West Space?

The body of work builds upon an interest in emerging technologies that support big data, and the ethical and cultural fall-out this has for the individual and the collective. There is a focus on the collection, use and misuse of personal data.

Broadly speaking there are 3 bodies of work. #1 is a series of 13 sculptures that approximate containers based on the idea of bird feeders.

#2 is a set of 9 monochrome works that are UV fades on archival blue- board cut into box designs. Archival blue-board is a standard packing material used in museum collections to protect and store cultural materials. The UV fading is a process that we have developed over a few years. It’s a subtractive process whereby we denigrate the pigment in either fabric or a material like archival card using powerful modi ed arc lights that produce a high amount of Ultra Violet radiation, much like that from the sun. Images are printed onto a thin clear plastic, which we then stretch tight and place over the card. The UV light then passes through the image on the plastic causing the light to fade the material. This allows us to create detailed tonal images, similar to exposing from contact negatives in dark- room photography.

#3 incorporates building and removing walls throughout the gallery space. This is something that we have done in exhibitions before but not at a scale that West Space provides. Parts of the pre-existing walls have been cut and removed of their cladding, revealing their stud-work and providing views through the walls. New walls of unclad metal stud have also been constructed throughout the space and we have modi ed the entrance to incorporate a one-way mirror.

Transforming and stripping West Space’s architecture has been an important element in developing this project. I get the sense that illusion and disorientation are important strategies for approaching your audience. Can you speak to why creating parameters for this kind of mindset to be induced are important?

Modifying the gallery space partly came out of the work made for a Monash University Museum of Art exhibition 'Technologism' back in 2015 titled 'Once mysterious, became secret then became private', where we tracked audience movements in the space using technology provided by a commercial analytics company. The work covered the entire gallery complex utilising small ceiling fixtures that looked like normal gallery infrastructure as the only physical sign of the work.

The spatial interventions at West Space carry on a similar idea in relation to human navigation, but with more physical outcomes. The strategy has been to create and shrink space at the same time; to give the impression of transparency and opacity – the one-way mirror entrance is a particularly direct gesture in relation to this.

We are also interested in the history and evolution of private spaces. For example, when chimneys were being introduced into homes, more beams and internal walls were required to structurally support a brick chimney on the roof. Before this, the fire was the central fixture of the home and everything revolved around one open area in order to keep warm and cook. Once the chimney became standard, so did the walls and the splintering of what was personal and private.

I wonder if the idea of hidden algorithms that drive online platforms is also relevant to how you have undone West Space’s built architecture – i.e. exposing the structural elements of the gallery to reveal the underlying framework of a system or a power structure ...

The initial rationale had to do with the physicality of the space and asking how we might want to frame these ideas and works, as well as how an audience might occupy the space. Thinking about audience behaviour, we eventually started seeing the spatial interventions as works themselves. It is interesting to think about the similarities between algorithms and building spaces for people to roam in. A lot of online platforms have the premise of freedom built in to how you interact with them. These freedoms act as the catalyst for understanding the user, and viewing their behaviour as something that is traceable and marketable. A lot of this potential comes from building social models where people feel empowered through their own agency to interact with others. This enables companies and individuals to gain deeper access into people’s behaviours and possible future behaviours.

Cambridge Analytica – a data-mining rm that this year was revealed to have surreptitiously influenced numerous political elections across the world – has been a key conceptual reference point for Open Window. What are the other significant moments of ethical and cultural fallout you think about as part of research into implications of technological advances?

Edward Snowden’s National Security Agency (NSA) leaks of 2013 comes to mind: exposing top-secret documents regarding operational details about the United States’ NSA and its international partners’ global surveillance of foreign nationals, as well as its own U.S. citizens. Equally disturbing was the public’s indifference, as if years of Internet conspiracy theories and action spy films had encouraged individuals not only to expect, but also to accept, the situation and give over to it completely – complacency due to convenience.

Having said that, shifts in technology have always brought fears and new cultural problems around privacy. Things change – something is gained but something is also lost. Printing press equals loss of oratory tradition, television kills radio, Internet inverts many economic models and social norms, and so on.

I’d like to unpack your interest in bird feeders as a metaphor further, and how this plays with the definitions of interiors and exteriors. Many of the other sculptures featured in Open Window have a similar disjuncture between inside and outside – coffin, chimney, security safe, tortoise etc. It also reminds me of your previous work that referenced Nasubi, a Japanese comedian who was challenged to stay alone unclothed in an apartment a er winning a lottery for a ‘show business related job’; a ordeal that lasted 15 months that was broadcast on Japanese TV. What do you think about the current divide between personal privacy and freedom of information – does it worry you?

We have had this unrealised work idea for the last four years or so that is simply to open up a gallery in order to attract pigeons, allowing the birds to come and go as they please. The pigeons act as audience and artwork rolled into one. We initially enjoyed the simplicity of the gesture however quickly realised that, in order to encourage engagement, you need to offer something of value. In the case of pigeons, this includes food, fresh water and shelter.

This gesture is not without several moral and ethical issues, which expanded our thinking to consider a broader issue: that there is always the potential for misuse and exploitation in any simple exchange. Pretty soon this led us to relate this situation to virtual places where people gather and come and go; places that offer something not unlike ‘sustenance’ and, in return, get something back from users in the the form of their personal data that can be utilised for advertisers or something potentially more nefarious.

Being able to understand the behaviour of the individual and groups before they do has been a key selling point for data analytics companies. Whilst companies like Cambridge Analytica now claim that they oversold their capability to shape outcomes, the idea still exposes a desire to gain access to the inner working of people’s minds. Data (and the industry that exists around it) appears to be in the business of mining your behaviour in order to reveal it back to you, or to show you that your individual traits have collective consequences.

Nasubi’s story is pretty unique to a time and a place. The rationale of the television producer that led him to put someone through those conditions had to do with creating catharsis for the viewing community. Japan was going through a recession and people were doing it tough. Being able to come home and watch Nasubi struggle meant people could say, ‘At least things aren’t as bad for me as they are for Nasubi’. It was a sacrifice of the individual for the betterment of the collective and, in a perverse and un- expected way, Nasubi got the fame he was seeking.

Returning to Once mysterious, became secret then became private (featured in Technologism), this work was the near invisible conceptual outcome of representing the accumulation of data. Multiple ceiling-mounted wi access points in the gallery were used to track the audience’s movements by triangulating their position non-invasively using their smartphone signals. The recorded data was stored in a hidden mini computer, serving as an archive of visitor engagement with the potential to be analysed. Conversely, Open Window addresses similar terrain in wide ranging form and imagery. The bird feeder series plays on the concept of a container: a closed form for archiving and storage that offers itself up by opening and allowing conditional access and use.

A recurring character in your practice that reappears in this this project (in its most full real form to date) is ‘Ciba the Ritalin Man’* who was utilised as a marketing tool for drugs to treat attention de cit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Can you expand on your interest in the contemporary condition of individual attention and consciousness?

We first used the character in an animated video work made in 2014 for the exhibition Idle Resources which focused on the idea of the ‘attention economy’ and fears around people being distracted or having less of an attention span, and just overall being more shallow and superficial than in the past. The character materialised as a result of our research into early marketing strategies for Ritalin, as well as our interest in what the drug is designed to do – i.e. to medicate for focus in individuals.

The reference statue was created in the 1970’s by Ciba, the original patent owners of Ritalin, with the view to be prominently located on a doctor’s desks as a means to promote and normalise the drug. The figure has two sides that analogise a patient before and after being prescribed Ritalin: one with an anxious worried expression and one beaming contentment and joy. We found this didactic view unsettling and pretty interesting.

For Open Window we have also revived another Ritalin promotional character from the same era that seems to be in the middle of a joyful dance; kicking his leg out and holding up his cane hat to reveal an opening in the top of his hollowed out head. This figure was presumably to be used as a desk penholder – a disconcerting notion when dealing with a stimulant that changes amounts of chemicals in the brain (namely dopamine) to a ect your mental state. Both these characters have been scaled-up and formed in three dimensions from photographs found online.

The idea of a diminishing ‘attention span’ became popularised in the early 20th century but it seems to us that this kind of reaction goes back further. Similar responses to big social changes can now be re-considered, particularly with regard to major shifts in the advancement of information technology. Developments such as the popular uptake of written language (reaching its apotheosis around 400BC) and the development of the printing press are good examples of events that brought about similar

concerns. In each era, there were worries that the excesses of information would lead to distraction, and that the loss of complexity and nuance found in established knowledge forms would lead to a shallowing of culture. It seems that when the way people consume information changes irrevocably, fears relating to ‘attention’ closely follow.

*Ciba is the name of the company with the original patent on Ritalin. As far as we can tell the Ritalin character did not have a name.

The UV fades evoke a ghostly presence. Do you think the mass accumulation of information and data that is occurring is impacting traditional ideas of memory and history? Also, can you expand on the choice of imagery in these works? What are you overlaying and why?

They do have an eerie feeling. There is the tension between the right to be forgotten, the ability to remove information from online platforms, and advocacy for freedom of expression and the opposition to censorship of any kind. Information and images can have permanence and omnipresence when everything has to be archived on large databanks and clouds. Its great to have access to all of this but it does come with limitations. The majority of such information comes in the form of screen-based photography, text, sound, video etc. Light and photography is the dominant way in which we receive this information, which limits understanding the more complex physical world and its context.

The UV faded works have a series of images overlaid. The images underneath come out of researching parties involved in the recent Cambridge Analytica scandal and various other platforms such as Netflix that utilise algorithms to build better services. The work Window (Sun Microsystems) came out of looking at the physical location of Facebook and learning that, when the company took hold of the property in Menlo Park, they repurposed the recently fallen tech giant Sun Mircosystems entrance sign by turning it around and rebranding the back with Facebook. The current entrance sign to Facebook’s HQ now contains a strange haunting motivator for the company; a reminder that you are never too big to fail.

The UV works are all titled ‘Window’ with a more descriptive title in brackets. Much of the imagery has been overlaid with silhouettes of light coming through a window frame. This is a nod to the process from which they have been made – casting ultraviolet light onto the surface of the card and fading the ink away in a sort of speeding up of the decay of time. It also references their position at West Space as wall pieces that exist amongst an interior that is illuminated by natural light through windows during the day.

You all first met while studying Art at RMIT TAFE in 2004. How and why did you decide to make work together? Also, what does it mean to you to practice as a collective? Has this been a political choice as much as it might be a practicality?

We studied together at RMIT and then at the Victorian College of the Arts. We started working together after sharing a studio over a summer break. The group formed organically, it didn’t have an agenda in mind when it began or even any want to show work. But in saying that, there are politics and specific reasons as to why we have worked together for such a long time (coming on ten years the end of this year). We try to make the work the focus, not that we work in a group. Working as collective privileges dialogue and community over the individual and their position. There are always politics working in groups.

—

This exhibition has been supported by the City of Melbourne and Creative Victoria. The project is part of West Space’s annual commission series, which invests in a local artist to create a new body of work. Open Window is the fourth iteration of the series, following Jason Phu (2017), Lisa Radford (2016) and Lou Hubbard (2015).

The artists would like to thank: Patrice, Sabrina and Thea, the West Space board and all the volunteers; Michelle, Darcey, Ife and Henri, and Scott from Aim Autographics.

Patrice Sharkey: Let’s begin with your starting point for Open Window. What are you currently thinking about and how have these ideas taken shape for this project?

Gavin Bell, Jarrah de Kuijer & Simon McGlinn: The title of the exhibition is Open Window. The window is a transparent boundary between the inside and the outside: a viewpoint from either out or in, an entry and exit for observation and light, but also a sort of vulnerability in terms of privacy and security.

This project feeds off our last solo at Gertrude Glasshouse titled, Entertainment is like friendship, that dealt with the growing tension of the public’s trust of personalising algorithms working on content platforms like Facebook, Google and Netflix, and a wider anxiety and acceptance of one’s digital footprint. The title, Entertainment is like friendship, is paraphrased from the Netflix culture text that the company has made available for potential employees. The text alludes to the concept of the content provider becoming so intimate with its consumers through big data that they are like a friend to their consumers.

Your work regularly weaves together a wide range of referents (virtual, visual, material and theoretical etc). Can you describe some of the key symbols, stories and objects featured at West Space?

The body of work builds upon an interest in emerging technologies that support big data, and the ethical and cultural fall-out this has for the individual and the collective. There is a focus on the collection, use and misuse of personal data.

Broadly speaking there are 3 bodies of work. #1 is a series of 13 sculptures that approximate containers based on the idea of bird feeders.

#2 is a set of 9 monochrome works that are UV fades on archival blue- board cut into box designs. Archival blue-board is a standard packing material used in museum collections to protect and store cultural materials. The UV fading is a process that we have developed over a few years. It’s a subtractive process whereby we denigrate the pigment in either fabric or a material like archival card using powerful modi ed arc lights that produce a high amount of Ultra Violet radiation, much like that from the sun. Images are printed onto a thin clear plastic, which we then stretch tight and place over the card. The UV light then passes through the image on the plastic causing the light to fade the material. This allows us to create detailed tonal images, similar to exposing from contact negatives in dark- room photography.

#3 incorporates building and removing walls throughout the gallery space. This is something that we have done in exhibitions before but not at a scale that West Space provides. Parts of the pre-existing walls have been cut and removed of their cladding, revealing their stud-work and providing views through the walls. New walls of unclad metal stud have also been constructed throughout the space and we have modi ed the entrance to incorporate a one-way mirror.

Transforming and stripping West Space’s architecture has been an important element in developing this project. I get the sense that illusion and disorientation are important strategies for approaching your audience. Can you speak to why creating parameters for this kind of mindset to be induced are important?

Modifying the gallery space partly came out of the work made for a Monash University Museum of Art exhibition 'Technologism' back in 2015 titled 'Once mysterious, became secret then became private', where we tracked audience movements in the space using technology provided by a commercial analytics company. The work covered the entire gallery complex utilising small ceiling fixtures that looked like normal gallery infrastructure as the only physical sign of the work.

The spatial interventions at West Space carry on a similar idea in relation to human navigation, but with more physical outcomes. The strategy has been to create and shrink space at the same time; to give the impression of transparency and opacity – the one-way mirror entrance is a particularly direct gesture in relation to this.

We are also interested in the history and evolution of private spaces. For example, when chimneys were being introduced into homes, more beams and internal walls were required to structurally support a brick chimney on the roof. Before this, the fire was the central fixture of the home and everything revolved around one open area in order to keep warm and cook. Once the chimney became standard, so did the walls and the splintering of what was personal and private.

I wonder if the idea of hidden algorithms that drive online platforms is also relevant to how you have undone West Space’s built architecture – i.e. exposing the structural elements of the gallery to reveal the underlying framework of a system or a power structure ...

The initial rationale had to do with the physicality of the space and asking how we might want to frame these ideas and works, as well as how an audience might occupy the space. Thinking about audience behaviour, we eventually started seeing the spatial interventions as works themselves. It is interesting to think about the similarities between algorithms and building spaces for people to roam in. A lot of online platforms have the premise of freedom built in to how you interact with them. These freedoms act as the catalyst for understanding the user, and viewing their behaviour as something that is traceable and marketable. A lot of this potential comes from building social models where people feel empowered through their own agency to interact with others. This enables companies and individuals to gain deeper access into people’s behaviours and possible future behaviours.

Cambridge Analytica – a data-mining rm that this year was revealed to have surreptitiously influenced numerous political elections across the world – has been a key conceptual reference point for Open Window. What are the other significant moments of ethical and cultural fallout you think about as part of research into implications of technological advances?

Edward Snowden’s National Security Agency (NSA) leaks of 2013 comes to mind: exposing top-secret documents regarding operational details about the United States’ NSA and its international partners’ global surveillance of foreign nationals, as well as its own U.S. citizens. Equally disturbing was the public’s indifference, as if years of Internet conspiracy theories and action spy films had encouraged individuals not only to expect, but also to accept, the situation and give over to it completely – complacency due to convenience.

Having said that, shifts in technology have always brought fears and new cultural problems around privacy. Things change – something is gained but something is also lost. Printing press equals loss of oratory tradition, television kills radio, Internet inverts many economic models and social norms, and so on.

I’d like to unpack your interest in bird feeders as a metaphor further, and how this plays with the definitions of interiors and exteriors. Many of the other sculptures featured in Open Window have a similar disjuncture between inside and outside – coffin, chimney, security safe, tortoise etc. It also reminds me of your previous work that referenced Nasubi, a Japanese comedian who was challenged to stay alone unclothed in an apartment a er winning a lottery for a ‘show business related job’; a ordeal that lasted 15 months that was broadcast on Japanese TV. What do you think about the current divide between personal privacy and freedom of information – does it worry you?

We have had this unrealised work idea for the last four years or so that is simply to open up a gallery in order to attract pigeons, allowing the birds to come and go as they please. The pigeons act as audience and artwork rolled into one. We initially enjoyed the simplicity of the gesture however quickly realised that, in order to encourage engagement, you need to offer something of value. In the case of pigeons, this includes food, fresh water and shelter.

This gesture is not without several moral and ethical issues, which expanded our thinking to consider a broader issue: that there is always the potential for misuse and exploitation in any simple exchange. Pretty soon this led us to relate this situation to virtual places where people gather and come and go; places that offer something not unlike ‘sustenance’ and, in return, get something back from users in the the form of their personal data that can be utilised for advertisers or something potentially more nefarious.

Being able to understand the behaviour of the individual and groups before they do has been a key selling point for data analytics companies. Whilst companies like Cambridge Analytica now claim that they oversold their capability to shape outcomes, the idea still exposes a desire to gain access to the inner working of people’s minds. Data (and the industry that exists around it) appears to be in the business of mining your behaviour in order to reveal it back to you, or to show you that your individual traits have collective consequences.

Nasubi’s story is pretty unique to a time and a place. The rationale of the television producer that led him to put someone through those conditions had to do with creating catharsis for the viewing community. Japan was going through a recession and people were doing it tough. Being able to come home and watch Nasubi struggle meant people could say, ‘At least things aren’t as bad for me as they are for Nasubi’. It was a sacrifice of the individual for the betterment of the collective and, in a perverse and un- expected way, Nasubi got the fame he was seeking.

Returning to Once mysterious, became secret then became private (featured in Technologism), this work was the near invisible conceptual outcome of representing the accumulation of data. Multiple ceiling-mounted wi access points in the gallery were used to track the audience’s movements by triangulating their position non-invasively using their smartphone signals. The recorded data was stored in a hidden mini computer, serving as an archive of visitor engagement with the potential to be analysed. Conversely, Open Window addresses similar terrain in wide ranging form and imagery. The bird feeder series plays on the concept of a container: a closed form for archiving and storage that offers itself up by opening and allowing conditional access and use.

A recurring character in your practice that reappears in this this project (in its most full real form to date) is ‘Ciba the Ritalin Man’* who was utilised as a marketing tool for drugs to treat attention de cit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Can you expand on your interest in the contemporary condition of individual attention and consciousness?

We first used the character in an animated video work made in 2014 for the exhibition Idle Resources which focused on the idea of the ‘attention economy’ and fears around people being distracted or having less of an attention span, and just overall being more shallow and superficial than in the past. The character materialised as a result of our research into early marketing strategies for Ritalin, as well as our interest in what the drug is designed to do – i.e. to medicate for focus in individuals.

The reference statue was created in the 1970’s by Ciba, the original patent owners of Ritalin, with the view to be prominently located on a doctor’s desks as a means to promote and normalise the drug. The figure has two sides that analogise a patient before and after being prescribed Ritalin: one with an anxious worried expression and one beaming contentment and joy. We found this didactic view unsettling and pretty interesting.

For Open Window we have also revived another Ritalin promotional character from the same era that seems to be in the middle of a joyful dance; kicking his leg out and holding up his cane hat to reveal an opening in the top of his hollowed out head. This figure was presumably to be used as a desk penholder – a disconcerting notion when dealing with a stimulant that changes amounts of chemicals in the brain (namely dopamine) to a ect your mental state. Both these characters have been scaled-up and formed in three dimensions from photographs found online.

The idea of a diminishing ‘attention span’ became popularised in the early 20th century but it seems to us that this kind of reaction goes back further. Similar responses to big social changes can now be re-considered, particularly with regard to major shifts in the advancement of information technology. Developments such as the popular uptake of written language (reaching its apotheosis around 400BC) and the development of the printing press are good examples of events that brought about similar

concerns. In each era, there were worries that the excesses of information would lead to distraction, and that the loss of complexity and nuance found in established knowledge forms would lead to a shallowing of culture. It seems that when the way people consume information changes irrevocably, fears relating to ‘attention’ closely follow.

*Ciba is the name of the company with the original patent on Ritalin. As far as we can tell the Ritalin character did not have a name.

The UV fades evoke a ghostly presence. Do you think the mass accumulation of information and data that is occurring is impacting traditional ideas of memory and history? Also, can you expand on the choice of imagery in these works? What are you overlaying and why?

They do have an eerie feeling. There is the tension between the right to be forgotten, the ability to remove information from online platforms, and advocacy for freedom of expression and the opposition to censorship of any kind. Information and images can have permanence and omnipresence when everything has to be archived on large databanks and clouds. Its great to have access to all of this but it does come with limitations. The majority of such information comes in the form of screen-based photography, text, sound, video etc. Light and photography is the dominant way in which we receive this information, which limits understanding the more complex physical world and its context.

The UV faded works have a series of images overlaid. The images underneath come out of researching parties involved in the recent Cambridge Analytica scandal and various other platforms such as Netflix that utilise algorithms to build better services. The work Window (Sun Microsystems) came out of looking at the physical location of Facebook and learning that, when the company took hold of the property in Menlo Park, they repurposed the recently fallen tech giant Sun Mircosystems entrance sign by turning it around and rebranding the back with Facebook. The current entrance sign to Facebook’s HQ now contains a strange haunting motivator for the company; a reminder that you are never too big to fail.

The UV works are all titled ‘Window’ with a more descriptive title in brackets. Much of the imagery has been overlaid with silhouettes of light coming through a window frame. This is a nod to the process from which they have been made – casting ultraviolet light onto the surface of the card and fading the ink away in a sort of speeding up of the decay of time. It also references their position at West Space as wall pieces that exist amongst an interior that is illuminated by natural light through windows during the day.

You all first met while studying Art at RMIT TAFE in 2004. How and why did you decide to make work together? Also, what does it mean to you to practice as a collective? Has this been a political choice as much as it might be a practicality?

We studied together at RMIT and then at the Victorian College of the Arts. We started working together after sharing a studio over a summer break. The group formed organically, it didn’t have an agenda in mind when it began or even any want to show work. But in saying that, there are politics and specific reasons as to why we have worked together for such a long time (coming on ten years the end of this year). We try to make the work the focus, not that we work in a group. Working as collective privileges dialogue and community over the individual and their position. There are always politics working in groups.

—

This exhibition has been supported by the City of Melbourne and Creative Victoria. The project is part of West Space’s annual commission series, which invests in a local artist to create a new body of work. Open Window is the fourth iteration of the series, following Jason Phu (2017), Lisa Radford (2016) and Lou Hubbard (2015).

The artists would like to thank: Patrice, Sabrina and Thea, the West Space board and all the volunteers; Michelle, Darcey, Ife and Henri, and Scott from Aim Autographics.

|

| ||||||||||||